Today’s Women in SF&F Month guest is Angela Mi Young Hur! I’ve been excited to read her first speculative fiction novel, Folklorn, ever since I read its description: “A genre-defying, continents-spanning saga of Korean myth, scientific discovery, and the abiding love that binds even the most broken of families.” Folklorn will be released in just a few days—on April 27!

In Folklorn, headstrong and ambitious scientist Elsa Park, whose prickly exterior barely hides her wounds, contends with her mother’s claim that the women in their line are cursed to repeat the narrative fates of their ancestors—otherwise recognizable as Korean folklore characters. My novel is mostly a realist family drama examining intergenerational trauma brought on by war, immigration, and racism, though there are also flourishes of the gothic, absurd, and fantastical. Most important, numerous Korean folktales are woven throughout that I reinterpret through first-person monologues of feminist fury and lament.

One of these retellings is based on an actual ancestral legend of my family, the Gimhae-Gim-Heo clan, explaining the origin of our surname through my ancestress Queen Heo Hwang-Ok, also known as Suriratna. (My surname “Hur,” like “Heo,” is one of many Romanizations for “허.” My second cousins use a different spelling. My parents and brothers initially used “Huh” as early immigrants in the U.S., later changing it officially before I was born.) Queen Heo’s story is recounted in the Samguk Yusa, a 13th century Korean chronicle of history and legend. But the story’s even older, by a thousand years, as the Samguk Yusa references its inclusion in the Garakgukgi (Record of Garak Kingdom), now lost.

Folklorn is about the inheritance of myth from parents and culture, how these stories shape our identity and our lives, whether we submit, challenge, or reject. So it was delightfully Easter-eggy to include an actual family legend in this novel about story-fates and folkloric ancestors. Moreover, I incorporate this legend because her story echoes many of the folktales that are important to Korea and interrogated in Folklorn. Spoiler alert: in several tales, water is where girls and women are drowned by others, or led to sacrifice themselves, or spied on while bathing and then abducted. But seen another way, water is also the site of transformation, rebirth, or portals to another world.

My surname-sake ancestress, according to the legend, was a princess from the kingdom of Ayodhya. (Most archaeologists and historians believe this to be Ayodhya in Northern India, though some believe it’s the Ayutthaya Kingdom of Thailand.) One day, the princess’s parents put her on a ship with red sails and sent her in the general direction of east because they’d dreamt that’s how their daughter would meet her future husband. (I too have been tricked by my Asian mother into a surprise date with her friend’s son at The Cheesecake Factory. “He works at Google and bought his mother a house!” she said, announcing he’d pick me up in a half hour so I better slap on some makeup.) Luckily for my ancestress, she wasn’t left drifting too long because King Suro of Geumgwan Gaya (a kingdom in what’s now Korea) also had a prophetic dream. Now this is where my mother and Wikipedia differ.

According to Mom, the King also sailed out to find his future Queen, a maritime meet-cute for the ages, two royal ships coming together as equals in the ocean between them. I believed my mom’s version was the only one until I researched for my novel as an adult. The legend as it’s described in Wikipedia is confusingly loaded with details of emissaries, slaves, a pitched tent and the removal of silk garments as offering to the mountain spirit. I use my mother’s version instead but bend it further to suit my thematic needs. Mom’s retelling is also quite telling in itself. That’s something I explore in Folklorn—not just the stories we inherit and create about ourselves, but also how much we reveal in what and how we tell these stories.

My parents grew up in a very patriarchal Korean culture that’s sexist, often misogynist. They also grew up during the Korean War, a trauma that instilled in them the ethos to protect your own and survive at all costs—which in war, especially a civil war, isn’t always compatible. Immigration, building a business, and raising a family, while surviving multiple muggings and a near-fatal assault, didn’t leave much time for personal growth, healing, or political awakening for my parents. A mantra I often heard in Korean while growing up was: “Eat and survive.” That was life. And yet my mother, who’d always been told that her greatest asset was her beauty and gentleness, whose ladies’ college in Seoul had been a glorified charm school preparing her for marriage, had in her own way railed and raged against the tyranny of Korean patriarchy. My mother didn’t raise me to be a feminist, not in name. She is still very much a product of her generation and culture. But she did want me to be strong and proud of being Korean, to know I came from a princess who arrived in a new country and became its Queen, who accepted the King’s proposal only on condition that two of her children bear her surname and pass it on.

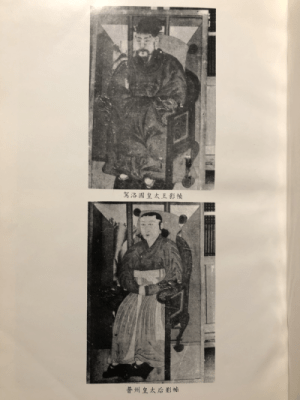

Painted portraits of Queen Heo and King Suro from our jokbo

Maybe my mom did put her romantic spin on the story for a reason—displaced yearning, wish-fulfillment? Maybe she wanted me to subliminally absorb that I should demand equal footing from my future partner, to be treated like a queen. I can’t project too much though because her feminism is one that’s been slowly developing. She’s eighty, still learning.

What I know for certain—why she told me this story, and about my great-grandfather’s great-grandfather who was a magistrate of Kaesong, and about so-and-so scholar-granduncles on my father’s side. Why didn’t I ask her about her own family’s stories until a few years ago? Wouldn’t she rather be telling me the story of her own ancestress queen? Her reply was that their clan wasn’t fancy, no remarkable people. Just landed farmers who made good money.

Truth is, I didn’t inquire further as a child because I didn’t fully understand the significance of these stories, not until I became an immigrant mother myself, with mixed-race immigrant children who look different from the other kids around them. I live in Stockholm, Sweden, with my Swedish husband. In telling the story of Queen Heo to my six-year-old daughter I understand my mother’s intentions more fully.

As a child, I was often bullied by the Japanese-American boys at my school who called me ugly and kimchi-girl and likely hated that I was the “smart one” in the class. (My novel also examines the complicated nuances of internalized racism and intra-racial prejudice, often rooted in history and hierarchal race structures.) Luckily, I had my father’s innate sense of pride / superiority, and the bullying didn’t erode my self-esteem too much, though it did make me sad, withdrawn, often mute. I certainly didn’t tell them to fuck off because I was a descendant of a queen. I shrugged off the story my mom told me, knowing I’d be humiliated and mocked at school if I mentioned it, since I was obviously not rich, not royal, didn’t look like anybody’s idea of a princess. Everyone knew my father ran an auto body shop in a “bad” part of town and sometimes teased me about that too.

But now, when I tell my daughter the story of our ancestress, I embellish with storytelling flair to impress upon my six-year-old the grandeur and beauty of her ancestral myth. My daughter is a fantasy and sci-fi nerd, who loved the movie Labyrinth at age four, read My Little Pony comics at five, plays Portal the video game, and draws dragons with ice powers. She’s the kind of kid who muses right before bedtime: “What if this is all a memory or a dream, and when we wake up, magic is real?”

I want my daughter to be proud of her Korean ancestry, especially as a mixed-race immigrant in Sweden. I want her to know she comes from a line of women who’ve braved new lands, exploring and learning and teaching. I want my daughter to know her name comes from an immigrant who became Queen, whose written story disappeared when the Garakgugki was lost, but was recovered, reclaimed, and reinforced in the Samguk Yusa, a thousand years later. During that millennium in between, how was this woman not forgotten? She became an oral story melding history and fantasy, compressed into gem, with facets of symbol and code—she became a myth so we could remember her and pass on her tale. And by sharing this with my children—a story told to me by their grandmother, who’s also a published essayist writing in Korean—they will understand why I gave them both “Hur” for their middle names.

I wonder why though I also deflate the magic for my daughter by telling her this queen’s descendants, bearing her name, number more than six million; that Korea was made up of multiple small kingdoms, so many can claim royal descent. I explain how legends are born from history and fantasy. I also show her our jokbo, official genealogy book, and explain how these have been meticulously recorded and preserved throughout Korean history, how our jokbo goes back over sixty generations and is our claim to the Gimhae-Gim-Heo clan. I don’t tell her that some jokbo were stolen or forged or bought into—just as noble names were purchased or self-given in Europe during the same time. I don’t go this far, but the impulse remains—to protect my daughter, from what? From believing too much in fantasy? Perhaps my child-self still worries what the other kids would say? Considering the genetic spread over human history, millions of us are indeed likely descended from Queens and Explorers, Adventurers and History-Makers—why can’t my daughter be one of them?

Fortunately, the story is not only shaped by the teller, but also by the receiver. My daughter tells her Swedish scientist father that she is descended from a princess who came by ship to Korea and became its Queen. And just last week, she wondered aloud if she and her brother should also pass on “Hur” as a middle name to their children. I’d never suggested this before, but I agreed it would be cool. This is how her mind works, absorbing the story and adding herself to it, wondering to whom she’ll pass it on.

|

Angela Hur received a BA in English Literature from Harvard and an MFA in Creative Writing from Notre Dame, where she won the Sparks Fellowship and the Sparks Prize, a post-graduate fellowship. Her debut The Queens of K-Town was published by MacAdam/Cage in 2007. Hur has taught English Literature and Creative Writing at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, in Seoul, Korea. She’s also taught for Writopia, a U.S. non-profit providing creative writing workshops for children and teens. While living in Stockholm, Sweden, she’s worked as a Staff Editor for SIPRI, the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. She is currently living in Stockholm, with her husband and children. |