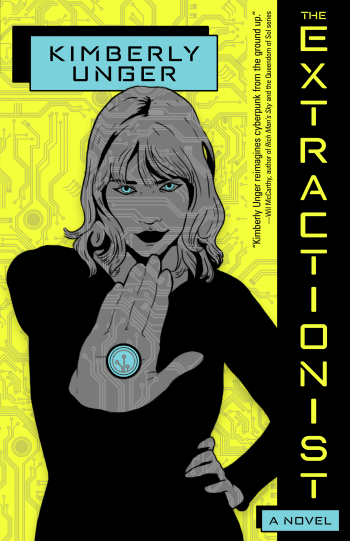

Today’s Women in SF&F Month guest is author and game designer Kimberly Unger! Her work includes the short stories “The Aborted Robot Uprising of TastyHomeThings” and “Wishes Folded into Fancy Paper,” as well as the science fiction technothriller Nucleation, her debut novel. The Extractionist, her sophomore novel publishing on July 12, features a hacker who extracts people unable to get themselves out of virtual space.

I’ve come to the realization that the idea of “dumbing down” needs to die.

Writing is research, pain and simple. Any topic you don’t have a personal expertise in (which is likely a LOT of things) takes a certain amount of asking questions. Way back when I first started learning to write I leaned into that way too hard. I write science fiction (and the occasional textbook) so the desire to provide well-researched, nuanced takes on future technologies is a strong one. I’d go so far as to say I do research sometimes just for the fun of it. The idea that anyone might not want to understand the difference between a fresnel lens and an optical pancake lens, even as a passing thought, keeps me up at night.

From talking to other new authors, it feels like this is not an uncommon problem. Anyone who’s working in a space that has some area of specialty feels this pain. You could be digging into corset making in the 17th century or researching bookbinding in the 18th. Faster than light travel? Bleeding edge automotive engineering? Any time I meet a starter author in a critique group or at a writing event, I hear the same concern.

“I don’t want to dumb it down.” Which is often followed by, “Readers are smart, they’ll know if I’m faking it.”

I know, in my case at least, this is a very “young” set of ideas that haven’t yet come in contact with the realities of finding an audience. Research leads to deeper understanding, not just of the subject matter itself, but of the way any given subject is commonly presented and understood. By doing the research, the author gets to see just how deep the rabbit hole goes. They consult the experts, read the material, and if they’re lucky, they get to hear all the cool stories. The job from there should be using this new understanding to add believability to the worlds and characters, but sometimes the desire to show just how cool the subject really is overrides the more pressing needs of the narrative.

And, because I’m just that kind of person, I started to examine my own fears around this process. What about this research, this deeper understanding, compels you to add more, to wander off into the weeds a bit as you craft your story? I mean, after all, we do the research in order to build a believable world. Why does that believability come with such a high narrative cost? Why is “dumbing down” the response we have as writers to something that is often intended to be a support piece, rather than the core of everything? And, as such self-examinations usually provide, I found a couple of recurring themes rolling around in my head. I don’t know if they’re in your head too, but let’s take a look.

But there’s so much more to know…

One of the things I run across is that the “popularly understood” version of a thing is often not at all nuanced. When you start to dig into something, well, to misquote a popular ogre, “it’s got layers.”

Source: I made this from a screenshot using Photoshop.

The reader, however, is often only familiar with the final image or the action they’ve been instructed to take. They are blissfully unaware of the handwaving that gets done in service of communication of an idea. Because, while it might be nice to know that radiation comes in a myriad of types, ranging from the optically pretty to the kill-you-dead, most people just know enough to put on sunscreen even if it’s cloudy. The depth and breadth of the subject matter has already, repeatedly been edited by experts down to the immediate day to day useful. To bring research into writing is merely a question of editing, something we writers are required to develop as a skill. We are focused on making a subject useful to our story and as such to our readers.

Those decisions you make around just what pieces of your research to include are not “dumbing it down,” they are making it more accessible.

Bringing the receipts

There is a certain hesitation in researching outside of your wheelhouse. Decades of being told to “stay in our lane” at work, at school, in society, on the freeway — okay, maybe it’s a valid criticism on the freeway — mean that many of us are nervous about getting called out for a misstep, or a factual error. Remember in the premiere of The Expanse, when Uncle Mateo pops open his helmet in a hard vacuum to readjust a wire, then closes it up again?

Source: https://www.syfy.com/the-expanse/photos/the-science-of-the-expanse-season-1-episode-6#196535

Where research is concerned, it feels like new writers try very hard to convey that right answer within the text itself. To stop the question of veracity before it even leaves a reader’s lips (or keyboard). This is especially true when the research we’ve done uncovers a fact or a figure or an image that goes against the idea most people have in their heads. In the case of The Expanse, it was the idea that a person could be exposed to hard vacuum and, well, not explode. After all, everybody knows that air pressure is what holds people together and if your suit gets opened up, then WHAMMO.

They got called out on it. It probably would have been nice if everyone had just shrugged and said “oh, they must have discovered something new about space,” rather than pointing fingers. But since they did their research, they had the more nuanced answer to hand (see “There’s so much more to know” above) when they needed it. Maybe not the perfectly correct answer, but their depiction was accurate enough once people started asking the question. This exchange turned into a moment of dialogue between the author and reader that wouldn’t have been possible otherwise.

It’s a dialogue, not a monologue…

It’s those dialogues, whether it’s on Twitter or around the dining table, that can illuminate just how effective making those facts accessible can be. Writing shares the same flaws as any other form of communication. In order to make valuable use of your research, you’re going to want to simplify it as much as the pacing and cadence of your story requires. Not because your readers won’t understand, not because you’re “dumbing it down,” but because you need to make that information accessible. Accessible engenders discussion and discussion becomes a teachable moment.

So do your research, distill it down and use it to support your stories. You’re not insulting anybody by simplifying. You’re not going to lose readers by failing to provide a three page explanation on the physics of magma to support exactly why a lava tube is on the lee side of the volcano for your hero to escape through. (Though, if you have access to that paper, could you send it along so I can have a look?)

The idea that a streamlined, accessible story can only be had at the expense of “dumbing down” your research needs to die. Once you’re past that, then your work really starts to live.

|

KIMBERLY UNGER made her first videogame back when the 80-column card was the new hot thing and followed that up with degrees in English/Writing from UC Davis and Illustration from the Art Center College of Design. Nowadays she produces narrative games, lectures on the intersection of art and code for UCSC’s master’s program, and writes science fiction about how all these app-driven superpowers are going to change humanity. [Unger writes about fast robots, big explosions, and space things.] She lives in the San Francisco Bay Area, where she works in the future of virtual reality on the Meta-Oculus gaming platform. |