It looks like 2018 will be a year filled with excellent books, and this is my longest anticipated release list yet with almost 30 books! Each and every one of them sounded too fantastic not to be on such a list, but I’m only showing the first 10 books on the main page due to the length of this blog post. You can click the title of the post or the ‘more…’ link after the tenth book to read the entire article.

This list only includes books that are currently scheduled for publication in 2018 (in publication order). If I couldn’t find news of the book’s release date on the author or publisher’s website, I did not include it even though I might continue to hope for its 2018 release (this includes The Muse of Nightmares by Laini Taylor and Monstress, Volume 3 by Marjorie Liu and Sana Takeda).

Without further ado, here are several books coming out this year that sound especially excellent!

The Lost Plot (Invisible Library #4) by Genevieve Cogman

US Release Date: January 9 (Published in the UK in Late 2017)

Genevieve Cogman’s Invisible Library series is so much fun, and I always look forward to each new installment. It follows Irene as she travels to various alternate worlds to acquire books (usually by posing undercover and then stealing them) for the organization known as the Library, which exists outside of time and space. I confess that calling this an “anticipated book” may be a bit of a stretch since it just came out and I recently finished it, but leaving it off the list didn’t seem right, either, considering it was a 2018 release I had been very much looking forward to reading. (And in case you’re wondering since I haven’t reviewed it yet—it is delightful and filled with dragons!)

After being commissioned to find a rare book, Librarian Irene and her assistant, Kai, head to Prohibition-era New York and are thrust into the middle of a political fight with dragons, mobsters, and Fae.

In a 1920s-esque New York, Prohibition is in force; fedoras, flapper dresses, and tommy guns are in fashion: and intrigue is afoot. Intrepid Librarians Irene and Kai find themselves caught in the middle of a dragon political contest. It seems a young Librarian has become tangled in this conflict, and if they can’t extricate him, there could be serious repercussions for the mysterious Library. And, as the balance of power across mighty factions hangs in the balance, this could even trigger war.

Irene and Kai are locked in a race against time (and dragons) to procure a rare book. They’ll face gangsters, blackmail, and the Library’s own Internal Affairs department. And if it doesn’t end well, it could have dire consequences on Irene’s job. And, incidentally, on her life…

Markswoman (Asiana #1) by Rati Mehrotra

Release Date: January 23

The description of Rati Mehrotra’s debut novel Markswoman immediately piqued my interest by mentioning “an order of magical-knife wielding female assassins.” After I finished The Lost Plot, I picked up this novel and was immediately hooked by Kyra’s test to become a Markswoman, and I continue to find the world and the different orders intriguing after having read about 80 pages. (I promise, this is the last book on this list that I’ve read or am currently reading!)

An order of magical-knife wielding female assassins brings both peace and chaos to their post-apocalyptic world in this bewitching blend of science fiction and epic fantasy—the first entry in a debut duology that displays the inventiveness of the works of Sarah Beth Durst and Marie Lu.

Kyra is the youngest Markswoman in the Order of Kali, a highly trained sisterhood of elite warriors armed with telepathic blades. Guided by a strict code of conduct, Kyra and the other Orders are sworn to protect the people of Asiana. But to be a Markswoman, an acolyte must repudiate her former life completely. Kyra has pledged to do so, yet she secretly harbors a fierce desire to avenge her dead family.

When Kyra’s beloved mentor dies in mysterious circumstances, and Tamsyn, the powerful, dangerous Mistress of Mental Arts, assumes control of the Order, Kyra is forced on the run. Using one of the strange Transport Hubs that are remnants of Asiana’s long-lost past, she finds herself in the unforgiving wilderness of desert that is home to the Order of Khur, the only Order composed of men. Among them is Rustan, a young, disillusioned Marksman whom she soon befriends.

Kyra is certain that Tamsyn committed murder in a twisted bid for power, but she has no proof. And if she fails to find it, fails in her quest to keep her beloved Order from following Tamsyn down a dark path, it could spell the beginning of the end for Kyra—and for Asiana.

But what she doesn’t realize is that the line between justice and vengeance is razor thin . . . thin as the blade of a knife.

Tess of the Road by Rachel Hartman

Release Date: February 27

Tess of the Road is set in the same world as Seraphina and its sequel Shadow Scale. That’s a pretty good reason to read it in and of itself, but it also sounds fantastic.

In the medieval kingdom of Goredd, women are expected to be ladies, men are their protectors, and dragons can be whomever they choose. Tess is none of these things. Tess is. . . different. She speaks out of turn, has wild ideas, and can’t seem to keep out of trouble. Then Tess goes too far. What she’s done is so disgraceful, she can’t even allow herself to think of it. Unfortunately, the past cannot be ignored. So Tess’s family decide the only path for her is a nunnery.

But on the day she is to join the nuns, Tess chooses a different path for herself. She cuts her hair, pulls on her boots, and sets out on a journey. She’s not running away, she’s running towards something. What that something is, she doesn’t know. Tess just knows that the open road is a map to somewhere else—a life where she might belong.

Returning to the spellbinding world of the Southlands she created in the award-winning, New York Times bestselling novel Seraphina, Rachel Hartman explores self-reliance and redemption in this wholly original fantasy.

If Tomorrow Comes (Yesterday’s Kin #2) by Nancy Kress

Release Date: March 6

Nancy Kress is one of my favorite science fiction authors since she excels at writing books with both interesting ideas and characters. Tomorrow’s Kin, an expansion of the Nebula Award–winning novella Yesterday’s Kin, is smart and compulsively readable with a compelling main protagonist, and I can hardly wait to read the next book in the trilogy!

Nancy Kress returns with If Tomorrow Comes, the sequel of Tomorrow’s Kin, part of an all-new hard SF trilogy based on a Nebula Award-winning novella

Ten years after the Aliens left Earth, humanity has succeeded in building a ship, Friendship, in which to follow them home to Kindred. Aboard are a crew of scientists, diplomats, and a squad of Rangers to protect them. But when the Friendship arrives, they find nothing they expected. No interplanetary culture, no industrial base—and no cure for the spore disease.

A timeslip in the apparently instantaneous travel between worlds has occurred and far more than ten years have passed.

Once again scientists find themselves in a race against time to save humanity and their kind from a deadly virus while a clock of a different sort runs down on a military solution no less deadly to all. Amid devastation and plague come stories of heroism and sacrifice and of genetic destiny and free choice, with its implicit promise of conscious change.

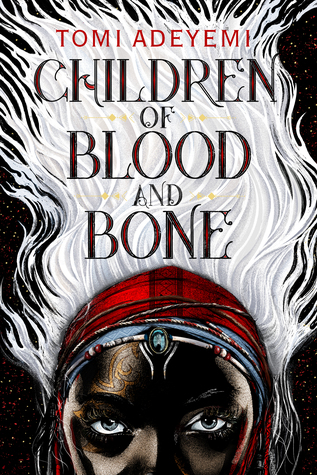

Children of Blood and Bone (Legacy of Orïsha #1) by Tomi Adeyemi

Release Date: March 6

It was the striking cover of Children of Blood and Bone that first caught my eye, and now I desperately want to read it because of the description. Everything about it sounds fantastic, including a heroine and rogue princess working together to outwit another!

Fierce Reads has an excerpt from Children of Blood and Bone if you want to take a peek at it while waiting for March.

Tomi Adeyemi conjures a stunning world of dark magic and danger in her West African-inspired fantasy debut, perfect for fans of Leigh Bardugo and Sabaa Tahir.

They killed my mother.

They took our magic.

They tried to bury us.

Now we rise.

Zélie Adebola remembers when the soil of Orïsha hummed with magic. Burners ignited flames, Tiders beckoned waves, and Zélie’s Reaper mother summoned forth souls.

But everything changed the night magic disappeared. Under the orders of a ruthless king, maji were killed, leaving Zélie without a mother and her people without hope.

Now Zélie has one chance to bring back magic and strike against the monarchy. With the help of a rogue princess, Zélie must outwit and outrun the crown prince, who is hell-bent on eradicating magic for good.

Danger lurks in Orïsha, where snow leoponaires prowl and vengeful spirits wait in the waters. Yet the greatest danger may be Zélie herself as she struggles to control her powers―and her growing feelings for an enemy.

Quietus by Tristan Palmgren

Release Date: March 6

Once again, I was first drawn to this cover with its beautiful colors, but I now want to read it because of its description: a transdimensional anthropologist chooses compassion over neutrality.

A transdimensional anthropologist can’t keep herself from interfering with Earth’s darkest period of history in this brilliant science fiction debut

Niccolucio, a young Florentine Carthusian monk, leads a devout life until the Black Death kills all of his brothers, leaving him alone and filled with doubt. Habidah, an anthropologist from another universe racked by plague, is overwhelmed by the suffering. Unable to maintain her observer neutrality, she saves Niccolucio from the brink of death.

Habidah discovers that neither her home’s plague nor her assignment on Niccolucio’s world are as she’s been led to believe. Suddenly the pair are drawn into a worlds-spanning conspiracy to topple an empire larger than the human imagination can contain.

Daughters of the Storm (Blood and Gold #1) by Kim Wilkins

US Release Date: March 6

Australian author Kim Wilkins’ Aurealis Award–nominated novel Daughters of the Storm will be published in the US this year, and it sounds fantastic: five very different sisters must work together for the sake of their kingdom.

Five very different sisters team up against their stepbrother to save their kingdom in this Norse-flavored fantasy epic—the start of a new series in the tradition of Naomi Novik, Peter V. Brett, and Robin Hobb.

FIVE ROYAL SISTERS. ONE CROWN.

They are the daughters of a king. Though they share the same royal blood, they could not be more different. Bluebell is a proud warrior, stronger than any man and with an ironclad heart to match. Rose’s heart is all too passionate: She is the queen of a neighboring kingdom who is risking everything for a forbidden love. Ash is discovering a dangerous talent for magic that might be a gift—or a curse. And then there are the twins—vain Ivy, who lives for admiration, and zealous Willow, who lives for the gods.

But when their father is stricken by a mysterious ailment, these five sisters must embark on a desperate journey to save him and prevent their treacherous stepbrother from seizing the throne. Their mission: find the powerful witch who can cure the king. But to succeed on their quest, they must overcome their differences and hope that the secrets they hide from one another and the world are never brought to light. Because if this royal family breaks, it could destroy the kingdom.

The Heart Forger (Bone Witch #2) by Rin Chupeco

Release Date: March 20

The Bone Witch is the story of a powerful necromancer who had no idea that she had these abilities until she unwittingly raised her brother from the dead, as told to a bard by Tea herself. Part of what makes Tea such a compelling protagonist is discovering the differences between her character in the past and the harder young woman met by the bard, and I’m looking forward to learning more about what happened to her to cause these changes. (Also, both books have gorgeous covers!)

In The Bone Witch, Tea mastered resurrection―now she’s after revenge…

No one knows death like Tea. A bone witch who can resurrect the dead, she has the power to take life…and return it. And she is done with her self-imposed exile. Her heart is set on vengeance, and she now possesses all she needs to command the mighty daeva. With the help of these terrifying beasts, she can finally enact revenge against the royals who wronged her―and took the life of her one true love.

But there are those who plot against her, those who would use Tea’s dark power for their own nefarious ends. Because you can’t kill someone who can never die…

War is brewing among the kingdoms, and when dark magic is at play, no one is safe.

The Queens of Innis Lear by Tessa Gratton

Release Date: March 27

Tessa Gratton’s upcoming fantasy novel inspired by King Lear sounds wonderful! (I am usually intrigued by fantasy books inspired by Shakespeare.)

Inspired by Shakespeare’s King Lear, dynasties battle for the crown in Tessa Gratton’s debut epic adult fantasy The Queens of Innis Lear, a story of deposed kings and betrayed queens

The erratic decisions of a prophecy-obsessed king have drained Innis Lear of its wild magic, leaving behind a trail of barren crops and despondent subjects. Enemy nations circle the once-bountiful isle, sensing its growing vulnerability, hungry to control the ideal port for all trade routes.

The king’s three daughters―battle-hungry Gaela, master manipulator Regan, and restrained, starblessed Elia―know the realm’s only chance of resurrection is to crown a new sovereign, proving a strong hand can resurrect magic and defend itself. But their father will not choose an heir until the longest night of the year, when prophecies align and a poison ritual can be enacted.

Refusing to leave their future in the hands of blind faith, the daughters of Innis Lear prepare for war―but regardless of who wins the crown, the shores of Innis will weep the blood of a house divided.

The Tea Master and the Detective (Xuya Universe) by Aliette de Bodard

Release Date: March 31

Aliette de Bodard described The Tea Master and the Detective on Twitter as “a gender-swapped Sherlock Holmes in space, with Holmes as an eccentric scholar, and Watson as a grumpy discharged war mindship.” I love this idea, the title, and the book cover and am eager to read more by Aliette de Bodard after being captivated by her latest Dominion of the Fallen novel, The House of Binding Thorns.

Welcome to the Scattered Pearls Belt, a collection of ring habitats and orbitals ruled by exiled human scholars and powerful families, and held together by living mindships who carry people and freight between the stars. In this fluid society, human and mindship avatars mingle in corridors and in function rooms, and physical and virtual realities overlap, the appareance of environments easily modified and adapted to interlocutors or current mood.

A transport ship discharged from military service after a traumatic injury, The Shadow’s Childnow ekes out a precarious living as a brewer of mind-altering drugs for the comfort of space-travellers. Meanwhile, abrasive and eccentric scholar Long Chau wants to find a corpse for a scientific study. When Long Chau walks into her office, The Shadow’s Child expects an unpleasant but easy assignment. When the corpse turns out to have been murdered, Long Chau feels compelled to investigate, dragging The Shadow’s Child with her.

As they dig deep into the victim’s past, The Shadow’s Child realises that the investigation points to Long Chau’s own murky past…and, ultimately, to the dark and unbearable void that lies between the stars…