The Leaning Pile of Books is a feature where I talk about books I got over the last week–old or new, bought or received for review consideration (usually unsolicited). Since I hope you will find new books you’re interested in reading in these posts, I try to be as informative as possible. If I can find them, links to excerpts, author’s websites, and places where you can find more information on the book are included.

There were a couple of slow mail weeks, which is why there hasn’t been one of these posts lately, but this week there are some intriguing books to feature including one recent purchase!

A Promise of Fire (Kingmaker Chronicles #1) by Amanda Bouchet

A Promise of Fire was just released in August (mass market paperback/ebook/audiobook), and I’ve wanted to read it ever since I first heard about it via a review on Angieville. It sounded like fun, and it sounded particularly intriguing given the comparison to the banter of the Kate Daniels series and the inclusion of Greek mythology (and, of course, because Angie has fantastic taste in books and has been influential in my discovery of some particularly good ones!).

Heroes and Heartbreakers has an excerpt from A Promise of Fire.

Catalia “Cat” Fisa is a powerful clairvoyant known as the Kingmaker. This smart-mouthed soothsayer has no interest in her powers and would much rather fly under the radar, far from the clutches of her homicidal mother. But when an ambitious warlord captures her, she may not have a choice…

Griffin is intent on bringing peace to his newly conquered realm in the magic-deprived south. When he discovers Cat is the Kingmaker, he abducts her. But Cat will do everything in her power to avoid her dangerous destiny and battle her captor at every turn. Although up for the battle, Griffin would prefer for Cat to help his people willingly, and he’s ready to do whatever it takes to coax her…even if that means falling in love with her.

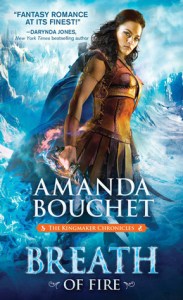

Breath of Fire (Kingmaker Chronicles #2) by Amanda Bouchet

The second book in the Kingmaker Chronicles trilogy will be released on January 3, 2017 (mass market paperback/ebook).

SHE’S DESTINED TO DESTROY THE WORLD…

“Cat” Catalia Fisa has been running from her destiny since she could crawl. But now, her newfound loved ones are caught between the shadow of Cat’s tortured past and the threat of her world-shattering future. So what’s a girl to do when she knows it’s her fate to be the harbinger of doom? Everything in her power.

BUT NOT IF SHE CAN HELP IT

Griffin knows Cat is destined to change the world-for the better. As the realms are descending into all-out war, Cat and Griffin must embrace their fate together. Gods willing, they will emerge side-by-side in the heart of their future kingdom…or not at all.

Crooked Kingdom (Six of Crows #2) by Leigh Bardugo

The first book in this duology, Six of Crows, will be reviewed later this month since it is this month’s Patreon selection. Shortly after finishing it, I purchased the next book, which was just released toward the end of last month (hardcover/ebook).

The Six of Crows duology page on the Grishaverse website has excerpts from both books.

Kaz Brekker and his crew have just pulled off a heist so daring even they didn’t think they’d survive. But instead of divvying up a fat reward, they’re right back to fighting for their lives. Double-crossed and left crippled by the kidnapping of a valuable team member, the crew is low on resources, allies, and hope. As powerful forces from around the world descend on Ketterdam to root out the secrets of the dangerous drug known as jurda parem, old rivals and new enemies emerge to challenge Kaz’s cunning and test the team’s fragile loyalties. A war will be waged on the city’s dark and twisting streets―a battle for revenge and redemption that will decide the fate of magic in the Grisha world.

The Immortal Throne (The City #2) by Stella Gemmell

This sequel to The City will be released December 6 (hardcover/ebook).

No one is safe, and no one is to be trusted as the bloody war that began in Stella Gemmell’s The City continues…

The dreaded emperor is dead. The successor to the throne is his nemesis, Archange. Many hope her reign will usher in a new era of freedom and stability. Soon however, word arises of a massive army gathering in the shadows of the north. They are eager to lay waste to the City and annihilate anyone—man, woman, or child—within it.

Yet just as the swords clang in fields wet with the blood of warriors, family feuds, ancient rivalries, and political battles rage on within the cold stone walls of the City. A hero must rise up and restore the peace before anything left to fight for is consumed by the madness.

Additional Books: